Margaretta

Russell Land, to give her the usual full married name was the natural sister of

Charles Taze Russell, two years his junior. As such she played a role in his

history, and ultimately was buried next to him in United Cemeteries, Ross

Township, Pittsburgh.

Below

is an extract from the official cemetery register as supplied by the current

owner. A number of names are deliberately obscured because many of these are

more recent burials and not our concern. But on this sheet for Section T, Lot

34, you can see that CTR was buried in Plot A, Grave 1. At the bottom of the

page, below the name of John Coolidge, who was buried at the end of the row and

whose name is inscribed on the famous pyramid memorial, is the name Margaretta

R Land. She is buried in Plot A, Grave 2, and the register states she was

buried on November 26, 1934. In reality her death certificate states this was

the day she died in New York City, and the interment took place in Pittsburgh

on November 29.

According

to the 1900 census, she was born in March 1854. She gave her testimony and

spiritual life story at the Niagara Falls convention in 1907 which readers can

easily check in the convention report. At the Praise and Testimony meeting led

by John A Bohnet on Sunday morning, November 1, she outlined her brother, CTR’s

story.

She

dated her own coming to a knowledge of the truth to “about thirty three years”

before, which would take us back to 1874, the year they would focus on for the

beginning of Christ’s presence (parousia). She also stated that Charles, his

father and herself were baptized that year, after coming to understand the true

import of baptism. She outlined how Charles at the age of 17 requested a letter

of dismissal from the Congregational church, which would be around 1869, the

year CTR was drawn to the “dusty and dingy” Quincy Hall in Lacock Street and

heard Jonas Wendell speak. She goes on with her lengthy testimony, well

expressed, and it is perhaps surprising that this is the only statement to be

preserved from her. As such, it is the only record we have for certain events,

so we have to depend on the memory of the single witness for the information.

At

some point in the mid-1870s she married Benjamin Franklyn Land, a cabinet maker

who worked in the Pittsburgh firm, Getchell and Land. Benjamin

appears to have shared the Russells’ religious beliefs at this time. George

Storrs, editor of The Bible Examiner visited a “small but noble band of

friends” in Pittsburgh in May 1874. In the June issue of his magazine he listed

the names of those who had requested literature, probably for distribution..

From The Bible Examiner, June 1874, page 288.

Familiar

names from Pittsburgh were Wm H Conley (2 parcels), G D Clowes Sen., and J L

Russell and Son (by Express). But slotted in between Clowes and Russell is B F

Land. We must assume that this was Margaretta’s husband or soon-to-be husband.

By

the 1880 census the Lands have two children, Ada (born November 1875) and Alice

(born November 1878). Another, Joseph Russell Land (born June 1880) was on the

way. A fourth child, May (sometimes called Thelma), would be born in February

1886, the year The Plan of the Ages came out. The 1900 census clearly shows

that Margaretta and the children were living in Pittsburgh when May was born. A

Benjamin F Land is still in Pittsburgh trade directories as a carpenter up to

1888, although this may have been his father.

At

some point disaster hit the family. Around

1954 an elderly Joseph Russell Land gave a testimony at a Bible Students’

gathering, which was recorded. His personal memories included living at CTR’s

home and also the breakup of his parents’ marriage. He didn’t take any real

interest in Bible Student matters until he was an adult when, more out of

curiosity than anything else, he went to hear his uncle speak after seeing an

advertisement. But as to his childhood years, he made these comments:

“I only lived with Pastor Russell for one year, and

that was with my sisters and my mother from 1887 to 1888, that was when I was

passing from 7 to 8 years old, and all I can remember of that was that we were

told not to go around – it was in a large house on a hill then - the Pastor

didn’t have the Bible House then – we children were told not go around on that

side of the house where Pastor Russell had his study, probably writing the

volumes…We didn’t go around on that side to bother him any.

“My dear mother being Pastor Russell’s sister, was

one of the first to come into the truth…My mother had just left my father in

Colorado Springs in 1887, and come to Allegheny with we four young children,

and we stopped with Pastor Russell for about a year and he took care of us.”

Reading between the lines, Joseph painted a picture

of Margaretta as a forceful character, somewhat obsessed with the great time of

trouble “just around the corner,” that he believed had a deterimental affect on

him as a child. But he conceded that her situation may have had a bearing on

that:

“It was a great time of trouble for a woman to have

four children, and no husband, to raise back in those days.”

We do not know why Margaretta’s marriage failed.

Taking her son’s words literally it was Margaretta who left Benjamin. It has

not been possible to trace what happened to him, but by the 1900 census

Margaretta is listed as a widow.

Living in the expanded Russell

household would have been a difficult time for everyone. Two forceful women in

the same household, Margaretta and Maria, would not be easy. Years later Maria

Russell would

make accusations against her sister-in-law in the Russell vs Russell court case

of 1907. These were put to CTR and quoting from page 229 of the transcript, his

cross-examination by Maria’s counsel went as follows:

Q: You know that Mrs Land was more or less

offensive to Mrs Russell?

A: I did not, sir, and do not know any reason

why she should be.

Q: Mrs Land had lived with you before, when you

and Mrs Russell had lived together?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And there was a constant source of trouble

between you and Mrs Russell about your sister?

A: No, sir.

Q: And did not Mrs Russell finally insist that

Mrs Land should leave the house?

A: No, sir, not that I remember of.

Q: Well, she did leave the house.

A: Of course, she left the house, and Mrs

Russell left the house too; Mrs Land moved down to her father’s, down in

Florida, she moved at that time.

Margaretta

and her children moved to Florida to be with her father, Joseph Lytle Russell. Referring

to this time in Florida Joseph Russell Land also testified that when she was

“up against it” CTR was “always ready to send her help.” We assume that Charles

Ball and then his sister Rose moved into the Russell household after Margaretta

and the children had left, although there could have been overlap. But then in

due course CTR and Maria moved into the Bible House. According to the history

marker at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Hall this was in 1894.

Joseph

Lytle ultimately came back from Florida to Pittsburgh and died in a Cedar

Avenue property in December 1897.

Prior

to his death Joseph Lytle wrote a new will in July 1896 (witnessed by E C

Henninges, J A Bohnet and Mrs O A Koetitz) which made a bequest to Margaretta (a

house, three lots and 25 acres of land in Florida) as well as providing for his

wife and daughter, Emma and Mabel. Emma was to inherit two houses, another lot and

various stocks and notes that she later claimed were worthless and Mabel

inherited a house and another lot. CTR was named as executor. This became a

bone of contention as perhaps evidenced by the three witnesses having to sign

another statement in October 1897 that Joseph Lytle was of “sound mind and

memory” when they witnessed the will. Joseph Lytle left certain unspecified debts,

and Emma argued later that her Cedar Avenue property could not be sold to pay these

debts before all the other bequests had been used up.

It

did not make for a very happy extended family.

In

the 1900 census Margaretta was still in Florida and now listed as a widow. Her

eldest daughter Ada had gone, having married a Thomas Wells in 1895. The

marriage would end in divorce and she later married a C H White. However, the

other three of her children were still at home, Alice was a school teacher, Joseph

a cigar maker, and May was still at school.

She

soon returned to Pittsburgh and worked at the Bible House. She is featured in

various events over the first decade of the twentieth century. We will review

these in date order.

In

testimony for the above quoted Russell vs. Russell hearing of 1907 (transcript

page 90), daughter Alice Land testified that she had both lived in and worked

at the Bible House for about six years. We can assume from this that Margaretta

and the two daughters went back to Pittsburgh to be part of the Bible House

family from about 1901. Unlike some of the other workers they lived on the

premises for some of the time, although the Russell vs Russell 1907 transcript

states they had one room for the three of them (second floor front) in the

house Maria occupied on Cedar Avenue (see transcript page 225).

Maria

and the Cedar Avenue property came to the fore in 1903, when Margaretta was

mentioned in connection with CTR’s domestic troubles. In that year, CTR

reclaimed the house that his estranged wife, Maria was living in at 79 Cedar

Avenue, Pittsburgh (now renumbered as 1004). Maria had left Charles in 1897,

first going to her brother Lemuel in Chicago, and then on return to Pittsburgh

to her sister Emma’s home. Emma had inherited 80 Cedar Avenue (now renumbered

as 1006) from her late husband, Joseph Lytle Russell. Today there is a history

plaque on the property, acknowledging his original ownership. It should be

noted that the two houses were a duplex, two homes that shared a middle wall.

It was one of a long series of ornate 19th century row houses, all

connected together along Cedar Avenue with a beautiful park on the opposite

side of the street. All of the homes as well as the park appear today almost as

they did 150 years ago.

As

noted above, Maria lived first with Emma at number 80, but when the tenants at

number 79 moved out, Maria took it over and lived there with her mother for

several years. This is where her mother Selena Ackley died in 1901. The paper

trail on the property is unclear, and it may be that it technically belonged to

the Watch Tower Society by this time, but as far as Maria was concerned it

belonged to her husband and his actions showed he believed that too. The three

story home was large so Maria also generated income by renting out rooms. When

she used her extra money to publish a tract highly critical of CTR he took the

house back in 1903, and put Margaretta in charge of the property. A room was

offered Maria on a legal footing, but perhaps not surprisingly she simply chose

to move back in with her sister Emma next door on the left side of the duplex.

In

1907 CTR wrote his last will and testament, signed and witnessed on June 29,

1907. It was printed in full in the December 1,

1916, Watch Tower, and also in the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper for November 29,

1916. Margaretta was mentioned in connection with the funeral arrangements.

DIRECTIONS FOR FUNERAL

“I desire to be buried in the plot of ground owned by our Society, in the Rosemont United Cemetery, and all the details of arrangements respecting the funeral service I leave in the care of my sister, Mrs. M. M. Land, and her daughters, Alice and May, or such of them as may survive me, with the assistance and advice and cooperation of the brethren, as they may request the same.”

Mrs.

M. M. probably stands for Margaret Mae or may even be a misprint; other records

at this time give her full name as Margaret (or Margaretta) Russell Land. Daughter

May (as Mae F Land) was one of the witnesses. Margaretta, Alice and May were

all still working at the Bible House at the time.

During

this time, she appeared in photographs taken at the Bible House. Below are two

that date from around 1907. The one on the left is part of a group photograph

taken in the Bible House Chapel, and on the right she is in the Bible House

dining room.

In

November 1907 she gave her detailed testimony at the Niagara Falls convention

that we have discussed earlier.

In

December 1908 the Watch Tower carried an advertisement for a booklet, The Wonderful Story of God’s Love.

Written by Margaret Russell Land this was an illustrated poem, not to be

confused with a similarly titled work by Maria Russell published in booklet

form back in 1890.

But

then she disappears from the regular narrative.

There

are two possible explanations for this. One is that in 1909 a rift occurred over

a change made by CTR over the understanding of the New Covenant. This caused some

to separate from the Watch Tower. It resulted in two new groups of Bible

Students, although they were separated by geography more than belief. The

better known one was in Australia with Ernest Henninges and his wife, the

former Rose Ball. But the American one resulted in several well known names

leaving association with Watch Tower. They included M L McPhail, the hymn

writer, and also Albert E Williamson. Albert had been a Watch Tower Society

director and his twin brother Fredrick was Margaretta’s son in law, having

married her daughter Alice.

Some

have suggested that Margaretta may have supported this breakaway movement with

other family members, although we lack documentary proof of this. Or it may

simply be that the 1909 move from Pittsburgh to Brooklyn caused her to relocate

back to the warmer climate of Florida to be near family members.

When

CTR died she was featured in a news item intending to travel to the funeral. From

the Tampa Bay Tribune (Florida) for November 2, 1916:

This

is a typical effort of a junior reporter of the day. She may have intended to

go to Brooklyn rather than Pittsburgh for the first part of the funeral arrangements

– we just don’t know because she’s not mentioned in the actual reports – but it

is a revelation that CTR died on a ranch rather than a train!

Margaretta

was supposed to be responsible for CTR’s funeral arrangements according to his

last will and testament, but that was back in 1907 and much water had gone

under the bridge since then. For example, editorial committee nominee John

Edgar had been dead for six years. There is anecdotal testimony that she may

have wanted funds for her expenses to attend the funeral, but since she had

inherited a house, three lots, and 25 acres of land in Florida from her late

father, and also had a family of four adult children who could have helped her,

that doesn’t seem realistic. Whatever happened, it is assumed that she did

attend the funeral, although the newspaper reports (including the St Paul

Enterprise) do not mention her. They do, however indicate that Maria and Emma

attended.

There

is, however, a photograph that long tradition identifies as her at the side of

her brother’s grave prior to interment. She is supposed to be the female figure

on the right, standing on her own rather than with other women higher up the

hill.

Without

corroborating evidence this just remains an unverified possibility.

After

CTR’s death, Margaretta lived out her life in Florida near daughters Ada (Mrs Ada

F White) and May (Mrs C Rea Kendall) until the year of her death, at which

point she moved to New York where daughter Alice Williamson looked after her.

But then at death she returned to Pittsburgh and was buried beside CTR. There

was no notice of her passing or funeral in the Pittsburgh papers, but she did

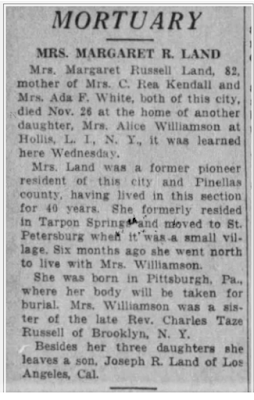

get an obituary in the Tampa Bay Times for November 29, 1934.

Again

we appear to have the less than accurate efforts of a junior reporter. Her age

is wrong, she was 80, she hadn’t been there for a continuous 40 years, and Mrs

Williamson was not the sister of CTR, but Margaretta was. All par for the

course.

So

Margaretta obviously had a long standing claim to the grave space beside her

brother. This was the only burial on the Society’s site throughout the 1930s. The

grave remains unmarked. It may be that no-one really remembered her in Society

history by then, or perhaps her family in Florida and New York did not see the

need, especially if they were never going to visit.

![Falcon's Crown: Kidnapped [e-book edition]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/a/AVvXsEhkBe00FOeBBmYbVCCTcdazS0iVnLd1WDFAqgsN2RZ54_2mWSQGowpbpnwmDREb-FVVk6AGpaGBEGezxxmeNm1qq65js_RZsBYwu6E6-3ucp3_YQyONvEK3NuIInA3Ru_cqrfm_JizezcrwPiewPQwunSXPJG1OI38N9mQwxOeGd4SvcPUf-DtO7FLMVcg=s238)