Guest post by Gary

According to historian Philip

Jenkins, in the United States “the most controversial religious group at the

start of the century was the Mormons”. However, he noted:

“The war fundamentally changed

that hostile atmosphere, as the Mormons showed themselves resolutely patriotic

and delivered impressively high recruitment rates to the forces. Old prejudices

faded.” (1)

In contrast, of course, and at

precisely the same time, Bible Students were showing themselves particularly

resistant to patriotism and indifferent to military support, so much so that

they “were accused of having crossed the line from anti-war sentiment to actual

treason.” Jenkins noted:

“In 1918, when federal and

state authorities were deeply concerned about pro-German subversion and

sabotage across the United States, much of their activity focused on

suppressing one densely packed theological rant, namely The Finished Mystery.” (2)

According to Jenkins “This work

included a fierce denunciation of war and nationalism.” (3)

Compared to allegations of

being unpatriotic, subversive and treasonable, on rare occasion Bible Students

of the era even found themselves vulnerable to lesser charges made, including

that they were guilty of food hoarding. How could this come about?

When food became political

Food hoarding has been beyond

the means of ordinary American citizens throughout history who, living lives of

subsistence, have usually lacked both the money and opportunity to

stockpile. In comparison, big business manufacturers, wholesalers

and retailers have been known to occasionally hoard and deliberately drive-up

prices to sell them later at considerable profit.

Concerned that the war would

encourage unscrupulous opportunists who might be intent on making a ‘quick

buck’, in August 1917 the US Government created the United States Food

Administration, headed by Herbert Hoover, and gave it powers to control the

production, distribution, and conservation of food. It was also responsible for

preventing monopolies and hoarding and so attempted to control the importation,

manufacture, storage, and distribution of foodstuffs.

Like it or not, food became

political. But whereas European nations embroiled in conflict resorted to

rationing policies, this would not be tolerated by Americans unused to feeling

the pinch of wartime hunger. Having joined the war in April 1917, the American

plan was to increase food production while decreasing consumption.

Consequently, the US Food Administration appealed to the patriotism of citizens

by promoting copious news articles, lectures and posters containing slogans

such as ‘God Bless the Household That Boils Potatoes with the Skins

On’. People were exhorted to plant victory gardens, to forgo wheat

(which could be easily shipped abroad), to substitute fish for meat (which was

expensive to produce) and to avoid wasting food. As a result, many observed

Meatless Tuesdays and Wheatless Wednesdays. And, of course, the making of

‘liberty bread’ was encouraged, making use of corn, oat, and barley flour

instead of wheat.

As one commentator noted:

“Modern warfare demands ... the

armed forces in the field and the arming-and-supporting force at home: it is impossible

to predict which is more important in securing ultimate victory.” (4)

Evidently, therefore, to many

the degree to which citizens adhered to these food measures was seen also as a

monitor to gauge their patriotism and support for the American commitment to

war.

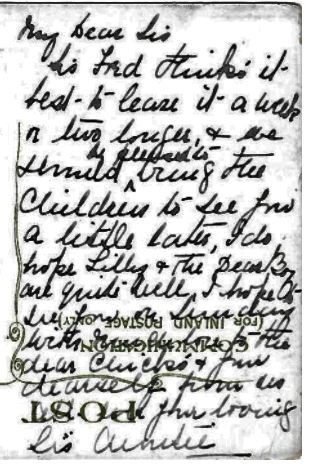

Poster

picture: Food is Ammunition-Don't waste it. Be Patriotic

Hoover could later report that the United

States had been able to ship far more food to Europe than had been expected,

and that this “could not have been accomplished without effort and sacrifice

and it is a matter for further satisfaction that it has been accomplished

voluntarily and individually.” (5)

Against such sacrifices on behalf of the

national goal, the idea of wealthy individuals hoarding valuable foodstuffs for

personal use seems greedy to an extreme. Consequently, is it any

wonder that, using the American Protective League, citizens are known to have

spied on and reported their wealthy near neighbors who were presumed to be food

hoarders?

Two unlikely food hoarders

Two unlikely people who

notoriously fell afoul of the US government’s laws on food hoarding in 1918

were Francis Smith Nash, US Navy Medical Director, and his wife Caroline Ryan

Nash, who on May 29, 1918, became the first people indicted on a charge of

violating Section 6 of the Food Control Act involving food hoarding at their

Washington DC home. (6) It was a serious charge and punishable, it

is said, by a two-year stint in a penitentiary or a fine of

$5,000. The case attracted considerable attention since Dr. Nash and

his wife were among the prominent in both naval and social circles. Caroline

and her daughter Miss Caroline (sometimes spelt ‘Carolyn’) were frequently

mentioned in the Society columns of the Washington press and lived and dined

among the capital’s social elite, President Wilson and his wife included. (7)

In an interview with the

Washington Times published on the following day, Caroline is recorded to have

said that the store of food found in the Nash home at 1723 Q street, northwest,

and which was valued by the Food Administrator at $1,924:16, was only the

regular order of things and the result of her usual policy of providing

liberally in advance for her table.

She maintained that the “long

and honored reputation of this family should be sufficient answer to this

absurd and ridiculous charge” and insisted “that we should be charged with such

an unpatriotic act as deliberately hoarding food is unthinkable.” (8)

Mrs Caroline and Dr. Frances Nash

Despite this, the authorities

insisted upon pursuing hoarders regardless of their social standing. Besides,

the Food Administration reasoned, if this wasn’t an example of food hoarding,

what was?

“I had no idea I was breaking

the law.” Caroline claimed. “We simply meant to provide for a rainy day. I

thought that one’s duty was to provide against a rainy day, and in order to

defeat the high cost of living one must buy in large quantities.” (9)

The more Caroline spoke the

more obvious it became that her household were indeed guilty, and the average

American reader who lived day by day on a basic wage can have had little

sympathy for the extravagant lifestyle of the wealthy Nash family.

As Caroline spoke carelessly to

the reporters, her husband Francis acted more prudently. The report stated that

he declined any statement for publication, as did his attorney. Indeed, he had

already appeared before Justice Stafford and given $3,000 bonds for himself and

Mrs Nash. However, in justification of the actions of the Food Administrator an

official statement significantly declared:

“The medical director has

admitted his violation. He said that in 1914 he inherited a legacy. With his

knowledge of probable conditions that would follow a prolonged war, he foresaw

a scarcity of food. So since the outbreak of war he had been investing his own

and Mrs Nash’s money in foodstuffs, storing them in his house against possible

years of great food shortage.” (10)

It was alleged that the food

stored was sufficient to maintain the family of Nash for more than a year and

far in excess of the requirements for thirty days, the period recognized by the

national Food Administration. At the trial Dr. Nash entered a plea of

“nolo contendere”, meaning that he neither admitted or disputed the charge and

did not wish to make a defence. Effectively he was neither pleading

guilty or not guilty. Much was made of the fact that 80% of the food products

found at Dr. Nash’s house had been purchased prior to the declaration of war

with Germany and practically all of the remaining 20% had been purchased prior

to the passing of the food conservation act. Even so, Dr. Nash was indicted by

the grand jury for food hoarding and, as a result, he was fined $1,000. Further

the hoarded foods were to be seized and sold accordingly at a public auction on

July 9, 1918, with the profits used to defray the legal costs and whatever cash

remained thereafter returned to Dr. Nash. Since Dr. Nash was found solely

responsible for the hoard, the charges against Mrs Nash were withdrawn

accordingly. (11)

The “hoarding of food supplies and the doctrine of the International

Bible Students’ Association”

By now you may be wondering

what has this episode, interesting though it is, got to do with Bible

Students? The Washington Evening

Star later reported further details concerning the charges against

the Nash family. Under the heading ‘Nash Food Hoard for War Haters’ it revealed

that some of the hoard “was intended for distribution among members of the

Washington branch of the International Bible Students’ Association as was

learned during the investigation that led up to the seizure”.(12) Much was made

of the fact that some of store was used to assist Bible Students, while nothing

was said, of course, about food supplied in the lavish soirées which Caroline

Nash had become famous for in the society columns of Washington press.

The District Food

Administrator, Clarence R. Wilson was quoted as having said that Dr Nash had

sent six barrels of flour to “a man in Brooklyn, named Haskins, an IBSA member

and that the garage to which the barrels had been sent was to a man named

Selin, a Finn, also a member of the International Bible Students’

Association.” Wilson pondered that “there may or may not be a relation

between the hoarding of food supplies and the doctrine of the International

Bible Students’ Association”, although he acknowledged that “whether Dr. Nash

is a member of that association I do not know.” (13)

Nash himself wisely declined to

comment, while later reports appear to distance him from any Bible Student

connection. His attorney, Prescott Gatley, for instance, spoke on his behalf in

court saying that his client had made application to the Navy Department to be

sent abroad and that he was anxious to do active service, but he had been

informed he was too old. The Washington Times commented that in this

manner Gatley “made an effort to dissipate the impression that Dr. Nash may

subscribe to the doctrines of the International Bible Students’ Association.”

(14)

So, was Dr. Nash ever actually

a Bible Student or was he just sympathetic to their teachings and helpful to

them? On the one hand, it seems unlikely that a Bible Student would

be so closely allied to the Navy. On the other, Nash’s role was that of a

medical officer whose service was one of healing rather than combat, and Bible

Student teaching at this time did not entirely preclude such a role. (15)

Consequently, it is presently impossible to say.

What then of the suggestion

that “there may … be a relation between the hoarding of food supplies and the

doctrine of the International Bible Students’ Association”? Under what

circumstances might wealthy Bible Students or their sympathisers somehow find

themselves in danger of being labelled a ‘food hoarder’?

Coming as it did during the

height of national hysteria involving Bible Students in the Spring and early

Summer of 1918, there was no way Nash’s reputation could entirely survive this

accusation. But given his connection, could there possibly have been

a motive other than simple avarice to explain his actions? Was he

simply planning on making a quick profit by selling his hoard at an inflated

cost when opportunity arose? Or might there have been another

reason?

Russell’s prudent foresight

To understand why a well-off

Bible Student, or even a well-to-do Watch Tower subscriber sympathetic to Bible

Student teachings, might collect such a food store we must consider the words

of Pastor Russell in late 1914, made long before America entered the war.

Believing that the Gentile Times had recently ended, Russell reasoned that the

near future would be extremely difficult for all, including Bible

Students. His Watch

Tower article of November 1914, entitled ‘The Prudent Hideth

Himself’ was based on Proverbs 22:3 and started:

“Let no one suppose that it

will be possible to escape the difficulties and trials of the great time of

trouble, whose shadow is now clouding the earth.” (16)

Russell encouraged readers to

heed four valuable lessons which might enable the wise to ameliorate future

difficulties. Firstly, application of Christ’s Golden Rule to treat others...,

secondly to show mercy, compassion, sympathy and helpfulness, thirdly to

display meekness, gentleness, patience and long-suffering, and finally, the

“fourth lesson should be economy in everything - avoidance of waste - the

realization that what he does not need, someone else does need.”

The article warned that bonds,

stocks and bank accounts may prove untrustworthy in the days to come but, in

line with Proverbs 22:3, it recommended “those having dry, clean cellars, or

other places suitable and well ventilated, to lay in a good stock of life’s

necessities; for instance, a large supply of coal, of rice, dried peas, dried

beans, rolled oats, wheat, barley, sugar, molasses, fish, etc. Have in mind the

keeping qualities and nutritive values of foods - especially the fact that

soups are economical and nourishing. Do not be afraid of having too much of

such commodities as will keep well until the best of next summer begins, even

if it were necessary to sell then, at a loss, to prevent spoiling.”

Significantly, the article

clearly explained the reason for this recommendation:

“Think of this hoard to eat, not

too selfishly, but as being a provision for any who may be in need, and who, in

the Lord’s providence, may come your way - ‘that you may have to give to those

who lack’ - Eph. 4:28”

At the same time as encouraging

this prudent measure, Russell exhorted readers “not to make these purchases on

credit if you do not have the money” and “not to sound a trumpet before you,

telling of your provisions, intentions” but to inform only your close family of

your planning.

Two things need be noted from this

article therefore. Firstly, it was a prudent measure designed for emergency use

only and not for personal profit. Secondly, its purpose was for sharing with

those who might suffer need. Retrospectively we may add that it was

a recommendation made nearly two and a half years before the US declared an

involvement in the war.

The article closed by reminding

readers “that the Golden Rule is the very lowest standard that can be

recognized by the Lord’s people and that it comes in advance of any kind of

charity.”

Seen in this context, Dr.

Nash’s actions become more understandable. He had inherited a minor fortune and

was likely a sympathetic Watch Tower subscriber with friends and contacts who

were Bible Students. His actions, taken prior to American involvement in the

war, may be seen as acting prudently in protecting his family’s interests and

as being in keeping with principles expounded by Pastor Russell to show mercy,

compassion, sympathy and helpfulness to others, appreciating that what he himself

did not personally need, someone else, at some later point, likely would.

Subsequently, it is not necessary to think of him as having hoarded food

entirely for selfish pleasure. At the same time, it is understandable why he

was charged with food hoarding and why, given the circumstances, he wisely made

a plea of nolo contendere.

It is not known if Mrs Nash

shared her husband’s interest in Bible Student teachings or indeed his IBSA

associates. For a while she seems to have kept a slightly lower profile in the

Washington society pages of the capital’s newspapers. Nothing more is known,

thereafter, of the Nash’s connections to the Bible Students while Mrs Nash and

her daughter Miss Caroline continued to live life in the public spotlight. A

Washington newspaper report from December 1930 commented that they were taking

their yearly winter visit to the capital having made their home in Paris,

France, some years back. (17)

References:

(1) The Great and Holy War,

Philip Jenkins, 236-237

(2) Ibid, 141

(3) “Spy Mad”? Investigating Subversion in Pennsylvania

1917-1918, 209

(4) Howard Anna Shaw, quoted in Marsha Gordon, “Onward Kitchen Soldiers: Mobilizing the Domestic during World War I”

Canadian Review of American Studies 29, no.2 (1999), 61-87

(5) Hoover, July 11, 1918, report to the President

(6) The Washington Times,

May 30, 1918, p1. Also, The New York Times of the same date.

(7) See, for instance, The

Washington Times, December 14, 1917, 16, which mentions Mrs Francis A.

Nash as being among several guests entertained by Mrs Wilson and given boxes in

a recital at the National Theatre. Mrs Nash was pictured and said to “post a

prominent role in Washington society.”

(8) The Washington Times,

May 30, 1918, 1

(9) Ibid

(10) The New York Times,

May 30, 1918

(11) The Washington Times,

June 15, 1918

(12) The Washington Evening

Star, dated June 16, 1918, p1

(13) Ibid. The “man in Brooklyn, named Haskins, an IBSA member” may have

been Isaac Francis Hoskins, a former director of the Watch Tower Society,

although he is known to have left Brooklyn on July 12, 1917

(14) Ibid, 2

(15) See Russell’s reply to an enquiry in Watch Tower, May 1, 1916, 142 [R5894]

(16) Watch Tower,

November 1, 1914, 334-335 [R5571-5572]

(17) The Washington Times,

December 18, 1930, 12

![Falcon's Crown: Kidnapped [e-book edition]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/a/AVvXsEhkBe00FOeBBmYbVCCTcdazS0iVnLd1WDFAqgsN2RZ54_2mWSQGowpbpnwmDREb-FVVk6AGpaGBEGezxxmeNm1qq65js_RZsBYwu6E6-3ucp3_YQyONvEK3NuIInA3Ru_cqrfm_JizezcrwPiewPQwunSXPJG1OI38N9mQwxOeGd4SvcPUf-DtO7FLMVcg=s238)